I’ve been thinking about Roadrunner cartoons lately, like you do.

Remember this one?

It’s fun to watch that coyote think he’s so clever - only to fall flat on his face. Har har!

Maybe we laugh because on some level we can relate. Haven’t we all been in situations where we expected X to happen, only to be surprised by Y?

That’s what happened to me when I first started writing for video games. And I’ve seen it happen to other writers, too - over and over again. We walk in the door, thinking that we know what to do, only to find out that we’re not as prepared as we thought.

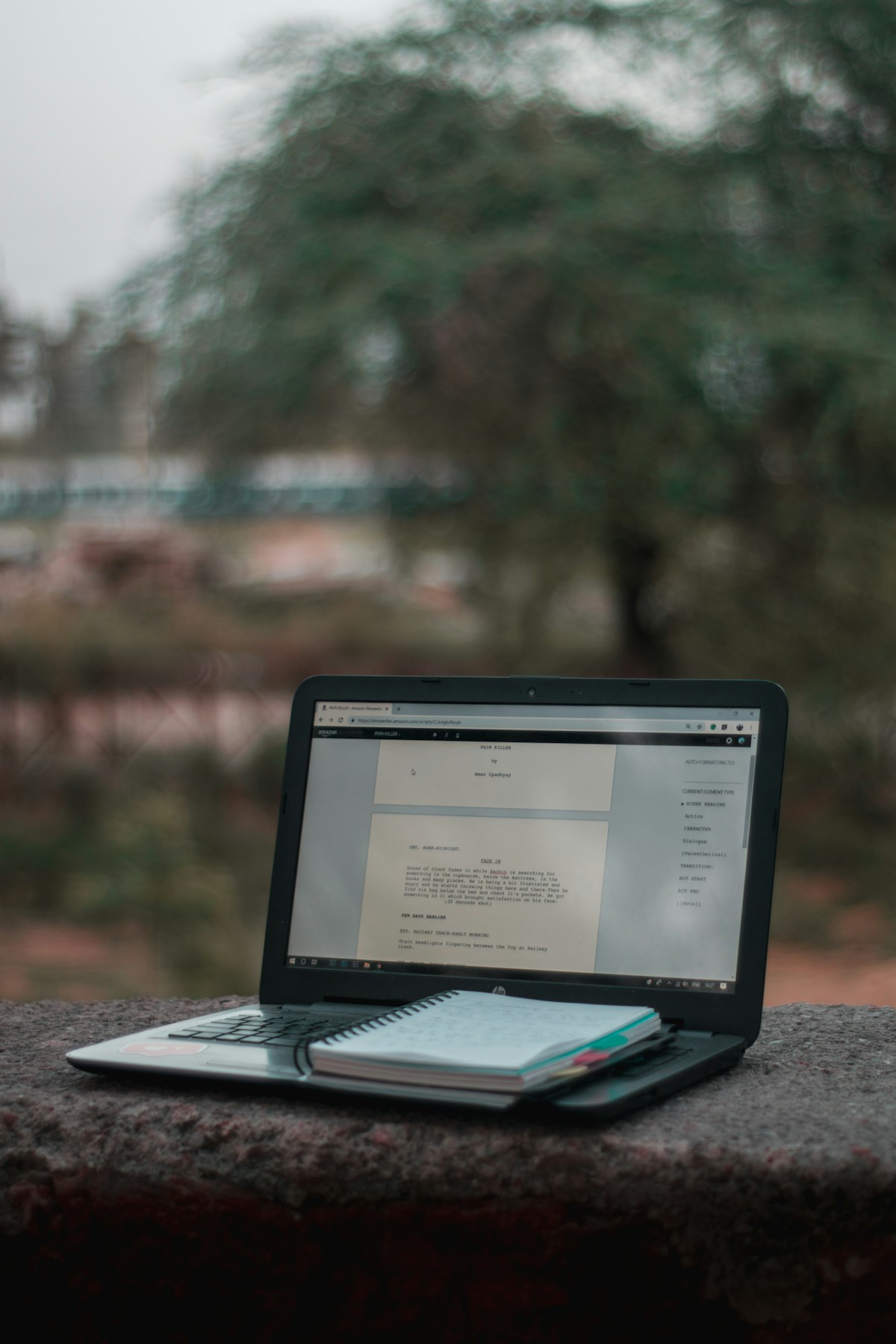

This is a problem that hits experienced writers especially hard. We get disoriented when things LOOK familiar but FEEL completely different. We see the scriptwriting software and the dialog and the voice actors and think “Oh yeah, I’ve got this!” - and then we crash into things like player agency and game mechanics and end up feeling a lot like poor old Wile E. Coyote up there.

Game writing LOOKS like screenwriting, or TV writing - but it is its own thing. It’s different in some very surprising ways. And that can trip us up.

At first, game writing seems to use a lot of the same tools as other forms of writing. Games feature characters, plots, and lines of dialog, don't they? Yeah, they do! So it’s easy to assume that what works in theater, or film, or TV will work in games, too.

And as writers, we want to do a good job. So we look for advice and examples. But most of the information out there is from other industries. There are so many books on screenwriting out there…and some of them are great! But they can lead us in the wrong direction. We’re not making movies here, people.

The truth is, as an industry we’re still figuring out what game writing is all about. We’re still trying to figure out our vocabulary, for crying out loud. We’re like a director from the 1930s, telling his cameraman “For this next shot, I want you to move real close to his face! Just keep the camera very close up to him during the scene. Know what I mean?” And someone eventually must have said “So you want a closeup?” And a new term was born.

(Fun fact: executives didn’t like this new closeup idea. Lilian Gish tells this story of when D.W. Griffith first started using the technique in his films:)

“The people in the front office got very upset. They came down and said: "The public doesn't pay for the head or the arms or the shoulders of the actor. They want the whole body. Let's give them their money's worth." Griffith stood very close to them and said: "Can you see my feet?" When they said no, he replied: "That's what I'm doing. I am using what the eyes can see."

Our industry is in a similar boat. We’re still experimenting with ideas like “character development through level progression” and “relationship between avatar and player.” They’re not tools we’re quite sure how to use yet - but we’re willing to try. These are probably features that are going to seem obvious in the future, but right now we’re still figuring things out. It’s a new world.

When in doubt, the trick is to use Zen mind, beginner’s mind - look at game writing through fresh eyes, and see what you find.

Here are three examples of how game writing is different other forms of storytelling:

The player is in charge

- What we assume: Story comes first

- What we discover: Player experience comes first

It's an interactive medium. The player doesn’t want to watch a story; the player wants to live a story. And teams find ways to create a playable story by prototyping game mechanics, trying things out, playtesting, and making changes based on results. This process inevitably breaks the story. And that’s a good thing, because it means the overall project will be better. When push comes to shove, the player experience matters most.

Game scripts are boomerangs

- What we assume: the writer writes a script and hands it to the team and then they build the game

- What we discover: There is no script handoff - it's not a relay race - everything is in a work-in-progress through most of production

There’s no “three drafts and you’re done" in game development! A game is a machine with a lot of moving parts, and those parts keep changing - and affecting other parts. That means if a level gets cut, the story may have to change. If a mechanic changes, could be time for a rewrite. Studios keep the writers busy throughout most of the dev cycle.

You’ll never write alone

- What we assume: The writers write the story

- What we discover: The writers co-create the story with lots of other people, most of whom are from other (non-narrative) departments

When story meets gameplay, that’s when writers meet designers (and everybody else on the team, too). At first, writers are surprised that so many other departments can weigh in on the game's story - writers usually prefer to work alone. But after a while that collaboration becomes a feature, not a bug. Smart game writers learn to chase down the animators, musicians, environment artists, and level designers in the studio, so that together, they can find ways to tell their stories as only games can.

This work is confusing until it's not. You keep at it long enough, it stops being confusing - and starts being fun.

Write great scripts with this free guide

Want to build up your writing skills? We can help. We've created an easy 5-step guide you can use to write scripts your players will love.

Best of all, it's free. Just click the button below!

Susan’s first job as a game writer was for “a slumber party game - for girls!” She’s gone on to work on over 25 projects, including award-winning titles in the BioShock, Far Cry and Tomb Raider franchises. Titles in her portfolio have sold over 30 million copies and generated over $500 million in sales. She is an adjunct professor at UT Austin, where she teaches a course on writing for games. A long time ago, she founded the Game Narrative Summit at GDC. Now, she partners with studios, publishers, and writers to help teams ship great games with great stories. She is dedicated to supporting creatives in the games industry so that they can do their best work.